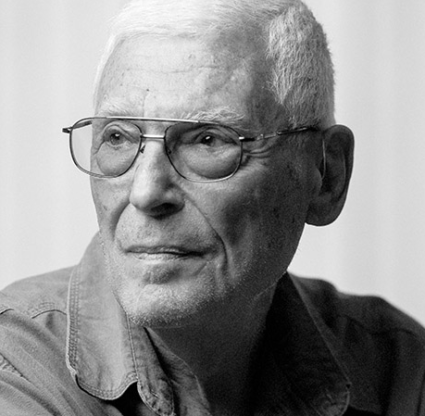

I’m standing on the 10th floor of a Fort Myers Beach condominium, staring out at 55 acres of wild expanse unlike anything this town has seen before. I’m here with Tom Taege, president of the Estero Bay Improvement Association, and Larry Siebert, who heads the EBIA’s maintenance, grounds and security committee. Taege is the retired owner of a farm equipment dealership in Michigan, and Siebert, also retired, was a real estate broker in Missouri. Both men are dressed in polo shirts and pressed khakis. They are an unlikely pair of conservationists.

As we admire the view, Siebert points to a stand of Australian pines in the distance. “Bald eagles like to sit up there and look out over the golf course—” He stops and corrects himself. “Excuse me. The vacant grounds.”

The grounds we are observing are indeed vacant, a lush space of greenery in a state somewhere between their previous incarnation as a golf course and their current role as a privately owned green space. In the community of Fort Myers Beach, where the debate over development has divided the island, the Estero Bay Improvement Association is doing something no one else has. It’s purchased a tract of land not intended to be built on. In fact, the EBIA is doing the opposite—the group has torn down the existing structures. A defunct pro shop and an old maintenance building are gone. So is the former sales office, a sprinkler shed and an abandoned restaurant. The golf cart paths that crisscrossed the former greens are growing over, and the sand traps are filling in with native grasses. The general shape of the golf course is still visible from this height, but it won’t be for much longer.

Typically, when we think of land set aside for preservation, we think of property managed by the government or nonprofit groups. The Everglades and Big Cypress both fall under the National Park System, and some of the better-known outdoor areas along the Gulfshore like Estero Bay Preserve and Delnor-Wiggins Pass are state parks. Sometimes land is purchased for preservation by organizations like the Conservation Fund, large not-for-profits that amass donations in order to buy and protect natural areas. But a group of private citizens using their own money to buy land they don’t intend to develop? That’s rare.

The Estero Bay Improvement Association is formed by the members of the 16 condominium associations that make up the complex off Bay Beach Lane on Fort Myers Beach. The 55 acres that once made up the complex’s golf course serve as a stormwater retention area, filtering runoff through a system of 13 lakes until the water is clean enough to enter Estero Bay. For years, the golf course was privately owned and the rainwater retention area was managed by the course’s owner under the direction of the South Florida Water Management District. But after a series of financial difficulties, the owner abandoned the property in 2014. Developers and investors started looking to scoop up the valuable real estate, and for the first time the EBIA considered purchasing the land and managing the retention area itself.

In order for that to happen, the condominium association would have to put the purchase to a vote. Seventy-five percent of the 1,235 units in the association would need to give their approval, and residents would have to pay for the land themselves. With a $2.4 million purchase price, that’s about $2,000 per household. Residents would also have to shoulder the costs of managing the stormwater system, an additional $150,000 per year. In the end, the proposed land purchase received a 96 percent approval vote, and the sale of the former golf course went through in December 2015.

“It wasn’t that difficult because the people back here wanted it to be a green space,” Taege says. “People didn’t want to see a bunch of other buildings. They didn’t want to see this island destroyed.”

At Fort Myers Beach town council meetings, one of the big complaints from residents is that new development is changing the face of the island.

“It’s not Old Florida anymore,” Siebert tells me.

“We’ve been able to preserve a piece of that right here,” Taege says. “We’re interested in keeping our water clean and bringing the wildlife back.”

The two men name the animals that have appeared since the EBIA bought the golf course and allowed it to revert to natural habitat: ospreys, hawks, owls, herons, ibises, alligators and iguanas.

“Which is not good,” Siebert says about the iguanas.

Taege chuckles. “Maybe the alligators will take care of them.”

Now that the purchase has gone through and the EBIA is in charge of managing the stormwater retention system, the question is this: What exactly should be done with the land? Some Bay Beach residents advocate for untamed wetlands for birds and native plants, while others want the acreage to be more intentionally managed with well-maintained walking paths and benches. A few members have even proposed some golf usage. Either way, Taege says, the goal is to establish a natural space for their community to enjoy.

Which raises another important question: Which community has access to this land? As it stands now, the former golf course is off-limits to the public, mainly, Taege says, because the association can’t afford to cover the liability on its insurance policy. Non-residents have been asked to leave the grounds on several occasions, and that’s created some hard feelings. If this were a green space managed by the government or a nonprofit group, then it would be open to the public. Because it’s privately held, however, not everyone gets to visit the property. Still, I’d argue that what’s essential here is the creation of a wild, natural space. More essential than the public’s ability to access it.

Though what the Bay Beach community is doing is rare, it’s not unheard of. In the tiny historic fishing village of Cortez, just west of Bradenton on Sarasota Bay, a group known as the Florida Institute for Saltwater Heritage, or FISH, performed a similar feat. In the early 2000s, the group decided to purchase a 93-acre tract of land first slotted for development in the 1950s. As neighboring natural spaces were turned into subdivisions, FISH recognized the urgency of protecting the acreage. Through private donations and fundraising efforts, FISH was able to raise enough for a down payment and has since paid off the note.

“Sarasota Bay only has two undeveloped properties left, and ours is one of them,” Jane VonHahmann, vice president of FISH, told me.

What FISH has accomplished, and what EBIA is accomplishing now, is to demonstrate the remarkable power of private citizens in conservation efforts. These are people who have taken direct, actionable steps to protect the environment. They’re not relying on elected officials or waiting on nonprofit groups. They’re doing the heavy work themselves.

I ask Taege and Siebert if they’ll walk me around the former golf course so that I can see what the land is like up close. We ride the elevator down to the parking garage and load into Taege’s Lincoln Town Car. He drives us to visit the lakes that make up the stormwater system and shows me the outflows where the clean rainwater empties into Estero Bay. We drive farther along, and he parks the Town Car where the old sales office used to be. Now it’s an empty sand parking lot. We climb out and walk to a white rope barricade.

“Come into the jungle,” Siebert says as we step onto the one-time golf course.

There are Mexican petunias and porter weeds, buckeye butterflies and yellow sulphers. A leaf blower whines from the manicured part of the condominium complex where an army of workers is tasked with trimming and mulching. Here, though, birdsong is the loudest noise.

“We’ve had a lot of roseate spoonbills come through,” Taege says. “Anhingas, too. And storks.”

The vegetation—cabbage palms, sea grapes, silver buttonwoods—is wild and untrimmed. Taege nods at our feet.

“There was a tee right here.”

It’s hard to imagine. From this vantage point, the concept of a golf course has all but disappeared. Instead there are inkberry bushes and cocoplums in a riotous overgrowth. The day is cloudless and clear, the sky a pale blue. As we walk back toward the sand parking lot, Siebert spots the green fronds of a coconut tree sprouting from a coconut.

“Look at this,” he says, crouching beside the young tree. “It’s amazing how fast Mother Nature can take back what man’s screwed up.