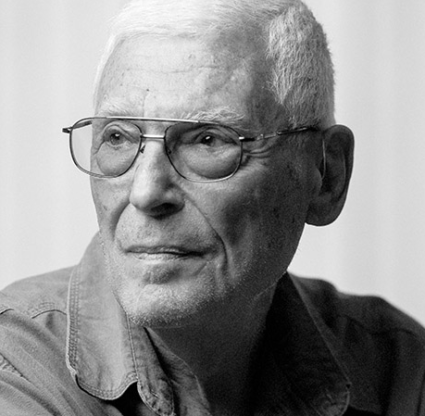

Michele Notturno, 73, sits poolside opposite her husband, Ken, 70, at a table on the back patio of their North Naples home. Only summers are spent at their condo on Gulfshore Boulevard North. A determined orchid blooms between them, rustled now and again by the March breeze. Their small boat is tugged gently by the water of the glittering lake in their backyard. Their dog comes up to greet them; their cat lounges nearby.

Soon the blue Friday sky would turn into what Ken would call a “paint by numbers” sunset behind his wife’s head, and they would debate where to go for dinner. It’s the pretty picture of retirement paradise that sends so many to our shores.

“I find it interesting,” Michele muses. “I was thinking about it. Thirty years ago I remember running a support group for grandparents raising grandchildren. And little did I think I would end up in the same situation.”

A closer look reveals hints of their roommate, 13-year-old Aubrey. Her spirited paintings line the walls, a basketball hoop completes the pool. They’re looking to sell that condo and move to a single location, with not senior living programs in mind but school districts. That boat once played part in an elaborate entrance to a Harry Potter party. The dog was a solution, years ago, for Aubrey’s persistent imaginary one. The choice of restaurant this night Aubrey is gone is kind of a big one, not limited to her teenage taste. And Ken is not retired; he works four days a week, in real estate project management and property development, because he has to.

Michele maintains her social worker license in Pennsylvania.

“I’ve been very aware of the situation and how it’s grown tremendously,” she says of grandparents returning to parenting.

As of the 2012 American Community Survey by the U.S. Census Bureau, more than 2.7 million grandparents were the primary caregivers to at least one grandchild. More than 4.5 million grandchildren, with and without their parents present, lived in a grandparent’s home. The situation arises regardless of the grandparents’ income level, culture, race, age, disability, marital status—and geographic location.

“We do see a rising trend of grandparents who are parenting their grandchildren,” says Elizabeth Morano, senior vice president of the United Way of Collier County.

The 2014 American Community Survey shows more than 2,500 grandparents in Collier County are responsible for their own grandchildren under age 18. And more than 3,700 in Lee.

“It’s a relevant issue because we’re seeing a lot of parental homes break down as a result of substance abuse and mental health and a combination thereof,” says Children’s Network of Southwest Florida CEO Nadereh Salim. Those are the two leading factors in our state and in our area, she says, that unite grandparent—more often than an aunt or uncle—and grandchild. But not the only ones. There are other illnesses, incarceration, immaturity, career paths, economic hardships, death. And to add fuel to the fire, there is a definite shortage of licensed foster care homes in Southwest Florida, says Vanessa Estrada, program manager at Friends of Foster Children Forever.

We recently talked to 10 grandparent families, five of whom share their stories here. They range from Lisa and Lester Adkins, who were left with their granddaughter when Lisa’s daughter unexpectedly passed away, to Jennifer DeFrancesco and Jerry Webster, who saw the plight of their grandson and firmly chose to step in. Here is some of what we’ve learned: Returning to parenting is exhausting, draining both physically and emotionally. It’s expensive. It’s life-altering. Some saw it coming, others didn’t. For those who actually want to talk—many don’t—there are no support groups. For those who need and will accept financial or material resources—many won’t—they are hard to find. Certainly there are no local organizations dedicated solely to this cause, or to answering those who are asking, “Where do I begin?”

Because for all of them, as they found when presented with this fork in the road, life didn’t exactly map out as planned.

She just wasn’t prepared to take care of her child,” Michele Notturno says of her daughter Amy, “when she was 19. Aubrey has been living with us since she was 1 year old, and Amy is mature enough at this point, even before now, to realize that we were the only parents that Aubrey ever really knew.”

Ken doesn’t understand why some people commend them for taking her in, that some people believe it was a choice. You do what you have to, he says. Family takes care of family. They’ve centered their lives around Aubrey just as they did their four children—this is no different.

Except, of course, for the ways it is. For one, the climate of social media is new. “We could just ground before!” Michele says. Now the cell phone is their greatest disciplinary tool. It’s tough with technology to balance access, now necessary for school and socialization, and control.

They’re now raising a child with difficulty developing self-confidence. They’re now raising a child in the same age range as their son’s. They’re now finding it tough to form friendships with classmates’ parents, because this time some are younger than their own children. Aubrey isn’t without embarrassment of the age difference. (“You’re gray!” she tells Michele of her hair. “Why don’t you dye it?”)

Having a young child keeps them young, Ken says, but it also makes them realize why you have a child when you’re young. (It wasn’t easy that time he worked into the night when he realized the day before Aubrey’s Rodgers and Hart project was due that they’d done it on Rodgers and Hammerstein.) And he finds he has to guard against a greater irritability than when he was younger. Michele finds she feels more isolated, with women her age doing different things and her day ending at 2:30 when she has to pick Aubrey up from school.

But that day is brighter, they say. They find joy in the wonder of Aubrey’s discovery, whether it be in her excursions with the Audubon Young Birders Club or her performances with the Naples Philharmonic Youth Chorus. They find joy in the experiences they wouldn’t have had without her, like spending the night on the floor of the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C.—Michele would have passed right on over that ad in the paper before.

The three of them celebrated Aubrey’s 13th birthday a day late this year with a special occasion. On Feb. 24, with the support of Aubrey’s mother, who remains in Pennsylvania, they formalized her adoption.

Aubrey’s behavior already reflects a new peace. She had lived with her grandparents nearly all her life, yet there was always that lingering feeling—would one of her parents take her back? Would her grandparents get angry with her and get rid of her? Kids imagine all sorts of things.

Now Mimi and Papa are Mum and Pops—not mom and dad, as Aubrey doesn’t want to hurt her mother’s feelings. Amy’s guilt has kept her from being a bigger part of Aubrey’s life, but that is changing. Aubrey still has little communication with her dad.

After Aubrey signed the adoption documents, she asked Ken anxiously, excitedly, for weeks if it was officially over and done. That felt good.

“It just reaffirmed what we were doing,” Ken says. “It made us feel comfortable we’re doing the right thing.”

|

|

Four-year-old Kendall is cared for by her grandparents Lester and Lisa Adkins. |

"She looks every bit of her mama. I had her mom’s baby picture and she said, ‘Nana where was I when I took this picture?’ And I said, ‘That’s not you, that’s your mother.’ Everybody was looking at them saying, ‘Oh my God, they look like twins!’ And Kendall has a gap in her teeth just like her mother.”

“Nana” is Naples resident Lisa Adkins, 46. She and her husband, “Granddad Lester,” who’s 59, are the legal guardians of their 4-year-old granddaughter Kendall, the daughter of Kenya, the youngest of Lisa’s three children. Her baby. Kenya passed away in a car accident just last September.

It’s not that Adkins isn’t used to watching Kendall. She has raised her most of her life, because Kenya had her child when she was still a child herself—at just 15. Kendall never was away for long. It’s just that now it’s permanent.

“It’s been tough because I’ve already raised my kids. My kids are big,” Adkins says. “It’s just been really tough, now that I can’t just call her mom when I’m tired and say, ‘Come get her.’ I have her all the time now.”

But she knows it in her heart, she says, that her daughter would “turn over” if she didn’t have her little girl.

She and Lester—Kendall clings to him, her “rock,” even more than she does to Adkins—both work full time, she as a patient care coordinator for a physical therapy center and he in maintenance for Collier County Public Schools, plus some lawn service on the side. Adkins turned down a higher-paying job for one with more flexibility. She has to be there, she says, to fill that void Kendall is feeling.

“As a little kid, people say she doesn’t know,” Adkins says. “Yes, she does know. She knows a big part of her is missing. Even though Nana is still here keeping her afloat, still a big part of her is gone.”

Kendall is a very busy 4-year-old. She’s painted the bathroom in nail polish, painted the car in hot coffee, broken eyeglasses, broken a statue. She’s full of stubbornness and full of sass: “No thank you, I think I’ll do that later.” Nap time? “She calls out like somebody’s taking her to war,” Adkins says. The times Kenya used to have Kendall, Adkins often would have to “rescue” Kenya when Kenya’s patience wore too thin. “I’m gonna go through it with this one,” Kenya would say.

“I looked up to the sky the other day and I told her, ‘No, I’m going through it! You’re not going through it!’” Adkins says, laughing. “I got your daughter! I’m going through it. But God won’t put more on you, and I know this for sure, than you can bear.”

She looks at Kendall and sees her daughter. And for every bit of nightmarish frustration, she sees “a little angel.” Laughs are certainly never far away. “Nana, put me down, you know you’re hurt!” she’ll say when Adkins tries to lift her with her bad shoulder. “Do you know what Nana did today? She said a cuss word on the way to school!” she spills to Lester after Adkins called some driver a jerk. And when Adkins comes home to find Kendall in timeout, and asks her how many times she’s been in the corner: “I don’t even know.”

Adkins certainly has her days when she breaks down, she says. But she also feels lucky. She knows not every grandparent has a supportive spouse who adores their grandchild; has friends to talk with and family to lean on; has even one steady job to pay the bills.

“I get up and go again,” she says. “I just get up and say, ‘OK, God, you need to help me through this. I need your strength in this today.’”

|

|

Jennifer DeFrancesco and her husband, Jerry Webster, are legal guardians to their 5-year-old grandson Daniel. |

Life in Naples used to be different for Jennifer DeFrancesco and her husband, Jerry Webster. But now it’s better.

Forty-three and 46, they traded spontaneity for school schedules, nights on the town for family nights in, retirement savings for college funding.

“I was done with all of it!” DeFrancesco says, laughing. “I had one child and done. That was my mindset.”

But when that child—her then-19-year-old daughter, Paige—needed help with her own child, Daniel, life switched gears. A single mother herself while raising Paige, DeFrancesco knew how hard it could be at a young age without a committed partner. But it was scary, the thought of making a choice that would change everybody’s lives. She still has to fight back tears when she remembers she had to separate Paige from her son. But she saw a struggle she couldn’t ignore. She said, “This is what I’m doing.”

Not a day has passed when she, or Webster, has questioned the verdict she made as a mother. Today, Paige is getting back on her feet. She’s involved in Daniel’s life, but DeFrancesco and Webster remain his legal guardians.

“It’s been such a huge benefit for everybody,” DeFrancesco says. “For my daughter to grow; for Daniel, I know he’s safe, I know he’s healthy, I know he’s taken care of. I just know I did the right thing.”

Two and a half years later, it’s fair to say little 5-year-old Daniel is the light of life for Webster and DeFrancesco—aka “Yo” and “G.” Talking to Webster about parenting Daniel, you’d think he had a new lease on life. The whole new world was hard at first, of course. (“Believe me,” he says, “if you want to find someone who was awkward, it was me.”) But grandparents who think taking on a grandkid is going to cramp their style shouldn’t bet on it, he says, because they will lose.

“I’ve had different businesses over the years and little accolades and whatever—it’s ridiculous how it pales,” he says. “If it’s not Daniel, nothing else counts. It’s amazing how a little kid can have that much impact on you. When you teach him something and you see it in his eyes? Wow.”

And teach him he has. Jujitsu, boxing, holding his breath to swim. Before that, it was how to brush his teeth, wash his hair, tie his shoes. He is his partner on Slurpee and Starbucks runs, his best friend—and, without question, his son.

Having to tote Daniel around “to look at houses” can be tough—they’re both technically on the job 24/7 as Realtors—but not always. In one home, DeFrancesco remembers, Daniel spotted a corded phone on the wall and had to ask what it was. Just picking Daniel up from school and hearing him say hello has the power to turn her day around.

She understands a lot of people feel that way about their children, she says. But loving a grandchild is, inexplicably, just “a different type of joy.”

Theresa Wheeler got the call in Pennsylvania. Nov. 28, 2014—her grandson’s ninth birthday. The Florida Department of Children and Families had been trying to track down Wheeler’s daughter because her two kids had been missing a lot of school. She called Wheeler from Immokalee, devastated, when they found her and took the children away to an emergency shelter.

From Pennsylvania, Wheeler pleaded with a Southwest Florida friend to attend an emergency hearing and get custody of RJ and MJ until she could return with her husband to Golden Gate Estates, where they were living six months out of the year since she retired from the sheriff’s office in 2012. They can’t split their time anymore, not with the kids in school.

“I went to visit the kids and went through the testing, everything (DCF) wanted me to do so that I could have the kids,” says Wheeler, 63, her faint voice barely audible over coffee shop din. She prays she has the strength to keep them until they’re grown.

“I think more grandparents should step up and take in their grandkids instead of letting other people foster them,” she continues. “It’s hard. It’s very hard, but you know what? Maybe God will pay you back one day.”

The hardships come in many shapes and sizes. Getting up early. Splitting up pre-teen arguments. It’s hard that 11-year-old RJ (short for Rejelio) is a little girl-crazy, and that MJ (short for Maryjane) cries because, legally, she isn’t allowed to see her mom. It’s even hard that Wheeler’s way of doing math is different from what the kids are being taught. If it weren’t for their tutor through Friends of Foster Children Forever, she says, she doesn’t know what she’d do. It’s especially crucial for MJ, who has Asperger’s syndrome. At 10 years old, she’s full of gray hairs, Wheeler says.

Finances are hard, too. At this age, the kids are always wanting to go here and there, do this and that. But there are bills to pay. FFCF has helped with birthday gift cards, Christmas shopping, school uniforms. It’s too expensive for Wheeler to add the kids to her insurance plan, but few doctors accept their Medicaid coverage. She gets just a little over $400 a month from the state in child support. She volunteers 15 hours a month at the Immokalee jail to keep her corrections supervisor certification, so she’s prepared to go back to work if, God forbid, something happens to her husband. David is 76, with severe back problems, and a survivor of stroke. Wheeler herself is borderline diabetic. There’s no help from RJ and MJ’s parents. Their father is in jail for human trafficking, but their mother is local.

“I look at her and I’m like, ‘Why? Why don’t you get your act together? What’s stopping you?’” Wheeler says. Her faint voice strengthens. “‘Why can’t you do what the courts are asking so that you can talk to them, be with them?’ I said, ‘You stole something from me. You stole my retirement from me. I have to start all over again.’”

It’s something they said they’d never do again after Wheeler’s oldest granddaughter, RJ and MJ’s half-sister, now 24, had come to live with them when she was 5. David retired from his job as a deputy to stay home with her. They raised her until she was 18—until her biological father came back into her life. It was very painful when she left.

“After that he told me, ‘There will be no kids in this house,’” Wheeler says. “But then this happened and he said, ‘We can’t let them stay in that (shelter). We can’t let anybody else adopt them.’”

Today is a different tune.

“It’s like the other Sunday,” Wheeler says. “Friday, Saturday and Sunday they stayed with my son, and my husband was like, ‘Don’t you think it’s about time you go get those kids? It’s too quiet in this house.’”

Candace Summers’ grandson came to her with nothing but a one-way redeye ticket, a book bag and a big smile for his grandma. He was 14 and too skinny, from a diet of ramen noodles.

She had a feeling she’d be taking him in again, because she’d done it before.

“My journey started with raising Dakota when I was 50,” she says. She’s now 66, and Dakota 17. “And the reason being babies having babies and drug and alcohol abuse with the parents.”

She’s quite familiar with the ways grandparents can come to raise their grandchildren—“separation of families, single-parent dwellings, babies having babies, substance abuse, loss of lives and life-changing situations”—as she’s writing a book on it. She hopes to publish the book, Broken Hearts, Broken Promises, and use a percentage of the proceeds to fund a local support group. Living in Cape Coral, she hasn’t found one. And where is the help for all the collateral damage? she asks.

She remembers an 86-year-old and 83-year-old walking into her place of business with their charges, ages 2 and 5. She meets plenty of others in her situation, she says, mainly through her profession. An esthetician, she walks the walk in a chic black fur vest, short-cropped blond hair, edgy teal-rimmed eyes, French manicured nails skimming her handwritten notes.

Her by-appointment flexibility has been a lifesaver with Dakota’s schedule. As a single grandma, it’s her only source of income. One relationship with a guy ended the first time she took Dakota in, after her daughter-in-law said she needed help when he was only 6 months old.

“I actually was told to make a choice,” she said. “It was either him or my grandson, and I said, ‘There’s no choice.’”

The second time he came to her, after Dakota’s father, her son, had a massive stroke, she made another sacrifice. She knew he wasn’t allowed to live with her and her significant other of 12 years in their 55-and-older gated community. Sure enough, soon there were complaints of hearing a child’s basketball, and they were forced to kick him out or relocate. Her partner begrudgingly agreed to rent another home. Two weeks later, though, he had had enough. Summers says it’s the best thing that ever happened to her.

Dakota hasn’t seen his mother in close to four years and sees his father maybe twice a year. Today that basketball bounces when he is troubled, the garage light sometimes flipping on at midnight. He wants to play college ball, but he’s had some setbacks. They’ve stemmed mainly from his self-esteem, which has taken a blow from difficult family events he won’t talk much about.

Summers taught him to play when he was 3 years old on her floor, moving a Playskool hoop back one tile as he mastered the distance and raising the basket as he grew. Her social life consisted of things like taking him to play at the YMCA. She’s in the other half of life, she says, so he should come first.

“And I’m willing to make more sacrifices,” she says. “Crazy, huh?”

Summers says a day may come when Dakota says he doesn’t need her help anymore, and that that’s his choice. But that doesn’t mean she won’t still be knocking on his door. And talking to these many grandparents, the message that they’d always be there if they could resounds.

Each of the families’ roads has been rocky. Some longer, some with more bends, each paved with stones they’d rather leave unturned and unexplained. But in the end, when they reached that fork, the decision was the same: It was the only road they’d take.